Animation enabled

Who rides the subway in?L.A.?

A healthcare worker on her way to the night shift. A rapper hoping his latest demo will get him on the festival circuit. An 85-year-old on his way to buy theater tickets. An aerospace worker part-way through a three-hour commute. A student “unfortunately” headed to a sketch show at Hollywood and Vine.

They’re your co-workers, your neighbors and some of the only people you can’t blame for making rush-hour traffic worse.

We meet them riding the Metro B Line on a Monday evening commute in November. (If you’ve lived here a while, you might still call it the Red Line.)

At 4:28 p.m., the train rolls out of Union Station. On board car No. 603 are eight passengers, plus a team of Times journalists. On the journey from downtown L.A. to North Hollywood, we try to interview every passenger in this car. When the train reaches the end of the line, we turn around and do it again.

Forty-six passengers agree to be interviewed; others say no. Sixty-eight passengers wear headphones, and 11 seem to be sleeping (we don’t bother them).

They come from all over.

Burbank, Chinatown, Chino Hills, downtown L.A., France (on vacation), Harbor City, Highland Park, Hollywood, Long Beach, Mid-Wilshire, North Hollywood, Pasadena, Pomona, South L.A., Van Nuys, West Covina, Westlake, Westmont.

They ride for many reasons.

To see friends. To settle an issue with a phone bill. To get home from high school or jury duty.

Most of the people we meet are commuters.

They work all kinds of jobs:

Social worker, construction worker, cleaner, aerospace engineer, financial analyst, hospital consultant, tile installer, chiropractor, commercial loans officer, paralegal, Chipotle grill chef.

Some rely on public transit because it’s their only way to get around.

Eight passengers tell us they don’t have a car.

Pam Dismond, 75, doesn’t like taking the train, but she doesn’t have a choice. A medical condition affects her eyesight and makes it impossible to drive. “I’m at the mercy of this,” she says, gesturing to her half-closed left eye.

But more riders say they take the train because it’s the easiest way to travel.

Some aren’t so lucky. We meet five passengers who say their trip is more than two hours door to door.

It takes Karen Pompa, 28, two hours to get between Pomona and her chiropractic externship. That gives her time to read “The Secret,” a self-help book by Rhonda Byrne. (She carries “50 Success Classics” by Tom Butler-Bowdon in her brown book bag.)

People pass the time in different ways: looking out the window, watching TikTok and listening to podcasts and music on their phones. Some passenger favorites:

“My Favorite Murder,” a true-crime podcast, “Trae el Cielo Aquí,” a gospel track by Barak, “Bongos” by Cardi B featuring Megan Thee Stallion, the alternative rock duo Twenty One Pilots, ranchera music, Frank Sinatra, Lana Del Rey

North Hollywood

Phones are a common distraction. When the train pulls out of North Hollywood headed to Universal/Studio City, 20 of the 44 passengers are looking at a device.

On the train, safety is a topic that comes up frequently.

Seven passengers tell us they have witnessed or been the victim of violence. Three others say they have been threatened on a train.

Laura Hernandez, 51, says someone on the train once approached her and demanded she give him the watch on her wrist.

“He told me, ‘I have a weapon, I’ll show it to you,’” Hernandez recalls.

She handed over the watch.

“Look at my hands now,” she says, stretching her bare wrists outward. “No more jewelry on here.”

Jenny Lin, 60, spends her commute murmuring Buddhist chants underneath her breath. “I am calling for Buddha. I am praying for my safety.”

Four passengers say things get wilder later in the evening.

Riding the train forces people to see the city, warts and all, in a way that driving doesn’t.

It goes to show these kinds of feelings about safety are highly personal.

Three passengers wish there was more security on the train. Five riders tell us they aren’t concerned about safety on the subway.

On his three-hour commute to Van Nuys, Ryan Castro, 57, feels safe. That’s not the case behind the wheel. He hasn’t driven since he got into a car accident.

Erika Perez, 41, didn’t have much experience with public transit when she started her new job as a paralegal in July. She was nervous.

But the more she travels this way, the better she feels.

“Plus,” Perez adds, she’s no stranger to self-defense. “I have a black belt.”

Cleanliness is a common complaint.

That said, no one blames Metro staff.

Metro ridership plunged by half at the start of the pandemic, but has since rebounded.

On an average weekday, 71,000 people ride the B Line or D Line (they mostly share the same route). Trains still aren’t as busy as they were before COVID-19.

Westlake/MacArthur Park

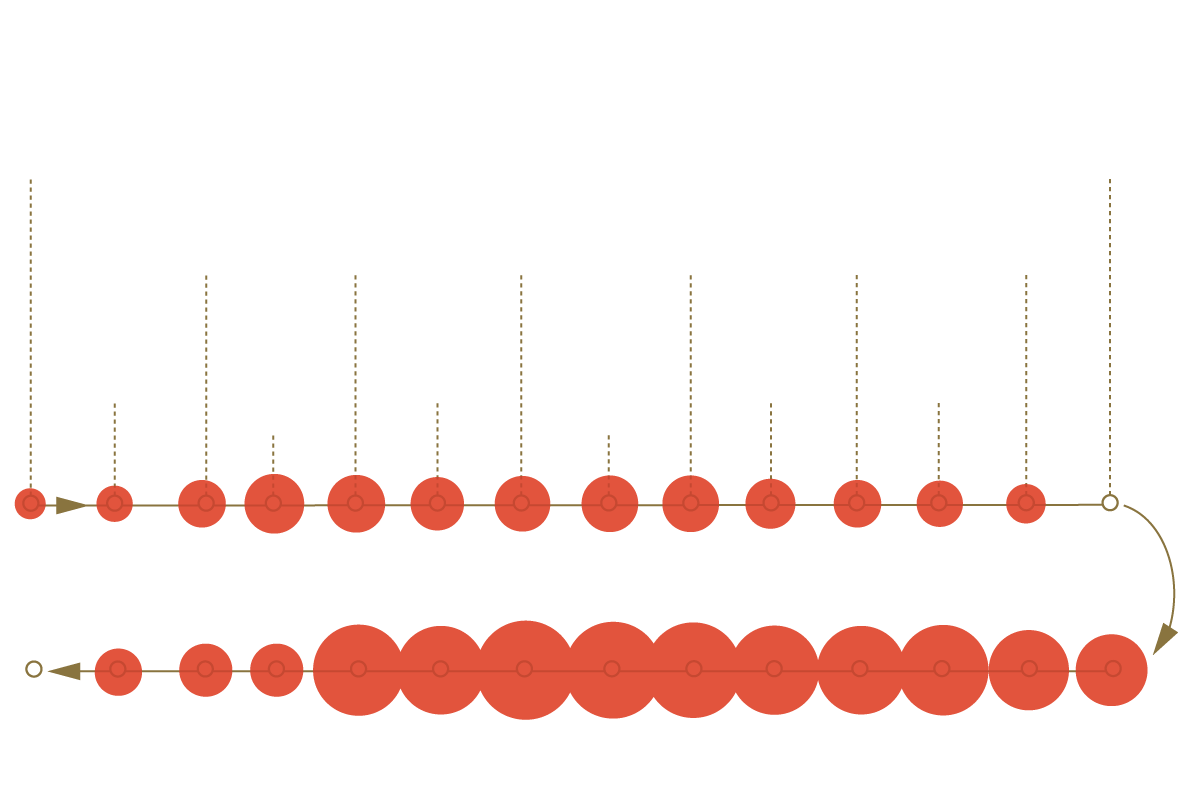

On our trip from Union Station to North Hollywood, ridership peaks at 30 passengers between the 7th St./Metro Center and the Westlake/MacArthur Park stations.

On the way back, things get much more crowded. Turns out the evening rush on the B Line heads toward downtown, not away from it.

When we depart North Hollywood, there are 44 passengers. Between Vermont/Beverly and Wilshire/Vermont, we share the car with 84 riders.

Metro Rail is just part of the agency’s transportation network, which provides nearly 1 million rides per weekday counting its buses and vans. That’s a lot of passengers, but L.A.’s jam-packed freeway system can make it feel like an afterthought. Less than 9% of Angelenos commute by public transit.

For those who have lived in other big cities, our mass transit doesn’t tend to impress.

They prefer the service in Chicago, Washington, London, Italy and France.

But then there’s one passenger who just moved here from Texas.

“I love it,” Katy Black, 26, says of Los Angeles’ transit system. “Coming from Austin, we don’t have anything like this.”

The train has a way of surprising new passengers and lifelong riders alike.

Devon MacNerland, 25, says he used to regularly cross paths with a vendor who would board the train with a special product: live turtles. “It’s turtle time!” the man would yell.

Passengers acknowledge that the transit system isn’t perfect.

Passengers offer an assortment of ideas that they thought would improve the system. They don’t all agree.

They suggest:

24-hour service, fewer delays, fewer odors, more trash collection, more reliable elevators and escalators, more security on trains and in stations, more effort to keep unhoused passengers from lingering, stronger crackdown on fare-skipping

But there’s a love and respect for it.

About a quarter of passengers who speak with us describe their train commute favorably. Official Metro stats say rail passenger satisfaction is even higher.

Either way, it’s not like car commuters are thrilled: Only 28% of Los Angeles drivers enjoy their commute, according to a 2020 survey.