EARTHseed Farm is unlike its counterparts among Sonoma County’s rolling vineyards and redwood forests.

A hand-painted sign at the entrance greets visitors with the words, “Welcome Black to the land.”

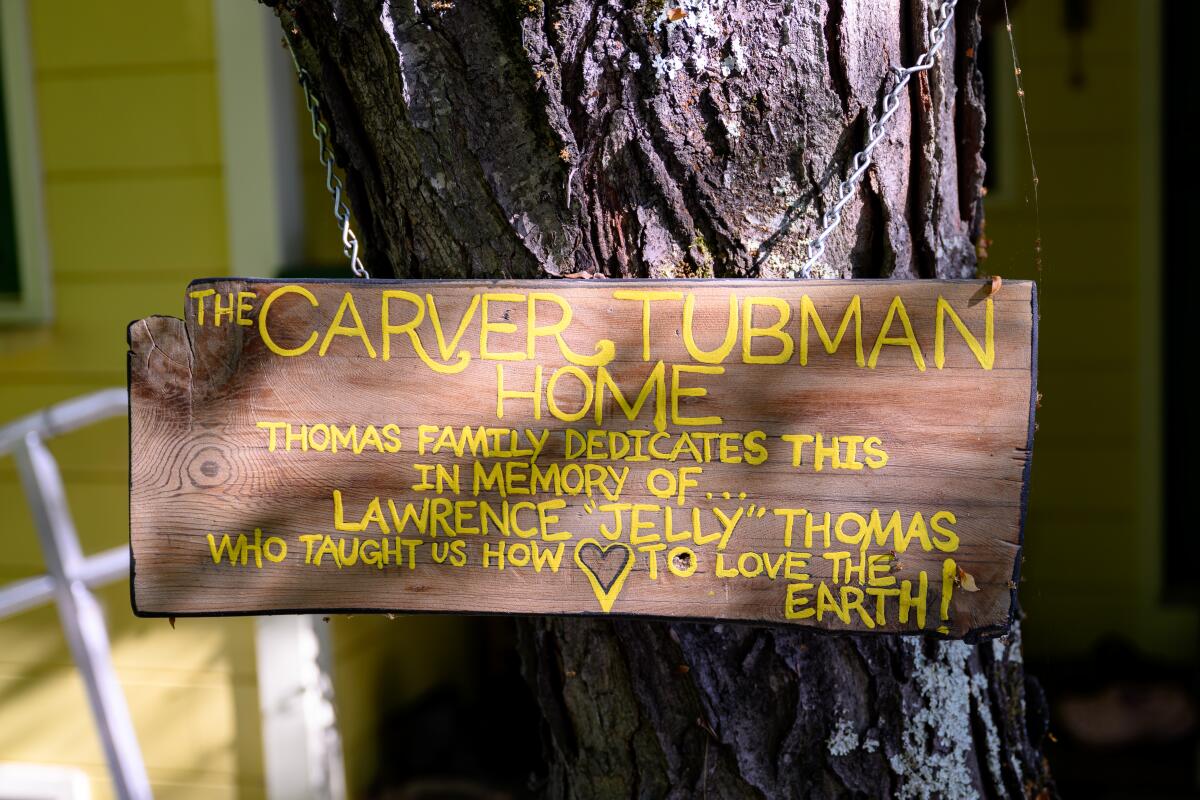

On the driveway to the two-story farmhouse that lies at the heart of the 14-acre property, another sign pays homage to the Black scientist George Washington Carver and the escaped slave who rescued scores from Southern plantations on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman.

A few steps away, a likeness of the late Black sci-fi author and Pasadena native Octavia Butler gazes from a mural painted on an outbuilding.

The Afrocentricity that radiates across EARTHseed is meant to make Black visitors in particular feel welcome — not an easy task in a county that is just 2.3% Black and where the average home price — $1.1 million — is out of range for most Californians of any race.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

For the farm’s founder, Pandora Thomas, there’s an even greater purpose. Thomas, a Berkeley-based naturalist and environmental educator, wants to teach her fellow Black Californians to use their African American heritage to usher their communities — and all of humanity — through the climate crisis.

Top: A sign honors George Washington Carver and Harriet Tubman at EARTHseed Farm, where people can buy freshly grown produce and take tours. Above: Founder Pandora Thomas stands near a mural depicting author Octavia Butler, whose 1993 novel, “Parable of the Sower,” had a huge influence on her. (Josh Edelson / For The Times)

What comes across as a hip U-pick fruit farm — one that is open to all — is also a laboratory for permaculture. It’s an approach to ethical land management and farming that’s widely embraced in California and that Thomas distills into three age-old principles: Be a good steward of the Earth. Take only the resources that you need. Pay it forward by sharing what you reap.

These values are urgently needed now, says Thomas, who often gives tours and workshops at the farm.

Black and brown Californians don’t just face an existential threat from ills such as racist violence, she says. Because of discriminatory housing practices that have crowded them into vulnerable ecosystems, generational poverty and a lack of access to land where they can grow their own food, their communities are also at greater risk from climate-related dangers: prolonged droughts, deadlier wildfires, flood-inducing rains, air pollution and the specter of water and food scarcity.

Jamaica native Winsome Pendergrass is part of a surge of immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean. She supports solidarity among Black Americans, but has been shunned in return.

“People look to Black culture for what’s the newest music, hair style or fashion trend,” says Thomas, 51. “Imagine if they looked to our communities for what’s the newest trend for how we should be living around climate practices and environmental practices.

“What can we garner from the past that we can bring to this moment to help us plot a better future?”

::

The temperature approaches 100 degrees one day as Thomas, dressed in denim shorts, a yellow T-shirt embroidered with butterflies and a wide-brimmed straw hat, invites visitors from the Booker T. Washington Community Service Center in San Francisco to cool off in the shade of an enormous willow tree.

“The cities that are having all of these heat waves, imagine if they had beautiful canopies like this, covered with natural trees to cool the air, soaking up water,” Thomas says, taking on the energetic tone of a motivational speaker. “Can we all just go to a leaf and thank Mama Willow?”

The group, a mix of teens and seniors, almost all of them Black, erupts in thank yous as the willow’s branches sway around them in the dappled light.

Thomas moves on to a patch of mulch next to a rainwater storage tank.

“African communities are some of the oldest communities that have captured water as it falls and not just let it go wherever it goes,” she tells the group, pointing to the absorbent ground cover and the tank.

“Many cities that are flooding are flooding because they’re full of hard surfaces that can’t capture, hold the water and direct it somewhere more beneficial.”

Next stop — a hexagonal bathhouse that’s reminiscent of a traditional mud dwelling in Africa.

“People of African ancestry were also the first people in the world to build structures with the earth — partly because we were the first people but also because where we lived was so hot,” Thomas says.

She urges her guests to touch the building and feel how cool its surfaces remain despite the blazing temperature.

“With all of these wildfires and this heat, we should be building with more earth — more resilient materials,” she says.

One of the seniors in the group can’t help but share her burst of African pride.

“We were the first engineers,” she exclaims.

For work, he tends roses at the Huntington. At home, he inspires his Watts neighbors with his low-cost, DIY garden full of native plants, herbs and food.

Thomas established EARTHseed as a nonprofit educational farm in 2021 in part to help fill a void. Although there are a number of established, Black-led permaculture programs in the Golden State, many Black Californians are not taught about their ancestral connection to sustainable land management and civic design, she says.

All across the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s Black homesteaders had set up communities and farms in an attempt to chart their own destinies — including in California — only for some of these settlements to be overrun, seized or burned down in racially motivated attacks.

EARTHseed’s setting — on the ancestral homeland of the Coastal Miwok and Southern Pomo tribes — is a sacred space for Black people to learn strategies for resilience. Indigenous Californians have for centuries resisted attempts to erase their culture and erode their connection to the land by holding true to ancient farming practices.

Angela Mooney D’Arcy of the Sacred Places Institute for Indigenous Peoples says Native Americans and other historically oppressed Californians should share in the fight for reparations.

The spirit of Butler, who’s been an inspiration to Afrofuturists and environmentalists alike, can be felt here too.

Her eerily prescient vision of 21st-century Los Angeles as a climate-disaster cautionary tale lies at the heart of her hugely influential 1993 novel, “Parable of the Sower.” Natural resources like clean water have been depleted, social upheaval and mob violence have driven residents with means into fortified compounds and abject poverty leads some to take extreme measures just to secure the basic necessities of life.

The protagonist, a young Black Angeleno whose community has been destroyed in the chaos, invents her own religion called Earthseed, whose “god” is change itself. She leads a group of fellow survivors to far Northern California, in the hope of starting over off the grid.

The novel is unflinching in its portrayal of the stark choices that Californians must make in a fractured society — and on a deteriorating planet. Thomas found the book terrifying when she first read it in 1999 while studying at Union Theological Seminary in New York. Yet, she said, there was also “a hope and glimmer in it — and nuance.”

Pomona native Victor Glover Jr.’s selection for NASA’s Artemis II moon mission isn’t just historic. His fellow Black Americans say it will change how the world sees them — and how they see themselves.

She was overcome with the desire to someday be a part of a community like the one in the novel.

The book also got her thinking about the lessons she learned in childhood about permaculture.

“My parents kind of espoused that because that’s also Black people ethics,” Thomas says. “We always helped everybody. My mom took care of the Earth, so we were kind of like Earth people. Her family were sharecroppers. ... So I feel like EARTHseed was just the culmination of that journey I was on when I read the book.”

::

Stepping through EARTHseed’s gates feels like a therapeutic homecoming for some of the community center visitors.

Several say that as Black people, they haven’t experienced such a close bond with the land since they were children visiting their grandparents’ farms in the Deep South.

“I didn’t even know that within an hour of my home in San Francisco, an urban environment that’s less than 6% Black, that I could literally come here to a Black-owned farm, that is Black-centric, where I see Black role models,” says Phyllis Bowie, 63.

Bowie grins as she maneuvers her hand into thorny blackberry bushes, where the dark fruits are ripe and hot to the touch. She plucks one and closes her eyes while biting into it.

“This is what I love — just me here, pulling off a berry and eating it, lowers my stress, lowers all of the racial biases that I live with,” says Bowie, who hosts a YouTube show in San Francisco about Black food sovereignty. “It all melts away.”

Bowie places her hand on her chest and tries not to cry.

She finds it profound that Black Californians, who fight so hard just to be respected for who they are, can also play a role in the discussion about the state’s climate future.

‘In these spaces, it’s safe to be us’: California’s Black trail riders, rodeo stars and ranchers find fellowship and spiritual freedom in rural traditions.

Bowie had once entertained the idea of buying farmland in rural Northern California but found the people too racist. Because of the example that Black farmers like Thomas have set, Bowie says, she plans to revive her search.

Shakirah Simley, the community center’s executive director, sees glimmers of the Black self-sufficiency that the Tuskegee University founder and presidential adviser Booker T. Washington envisioned more than a century ago and that Butler depicted in her writing.

The community center works with Black farmers such as Thomas to source fresh, organic produce for its food-giveaway programs. Simley, 38, uses field trips to places such as EARTHseed to go a step further — to show what Booker’s and Butler’s visions can look like in the present.

“It helps us make sure that we know that we can define our own future and make our own way and preserve our own agency,” she says.

While Thomas introduces the group to the resident pigs who act as a sustainable food-waste disposal system, farm manager Brent Walker walks down rows of crops to inspect ripening apples and Asian pears and check for leaks in irrigation hoses.

He says EARTHseed is lucky because the land’s previous owners had already incorporated sustainable practices to grow crops, as evidenced by the deep swells, or trenches, they dug between rows of Asian pear and apple trees to capture and hold rainwater during the wet season.

The farm is still susceptible to climate change, he says.

Walker, 44, takes an apple in his hand and points to a dark-brown blister the size of a silver dollar on its reddish skin.

“Sun burn,” he says. The excessive heat is dangerous for his fruit trees.

He spots another burned apple, then another.

Damaged fruit is less appealing to the local businesses, farmer’s markets and visitors that buy EARTHseed’s produce.

Making the farm less susceptible to the harms of climate change is still a work in progress, Walker says as he dabs sweat from his brow, the sun beating down on his bare chest. But he feels buoyed by the farm’s larger mission.

All too often, both he and Thomas say, Black Americans are portrayed as mere victims of inequity and injustice, even though historically they’ve shown a capacity for transcending their circumstances.

“Having that spirit of self-reliance and wanting to make something out of nothing, it’s in all of us,” Walker says.

He says it’s impossible to walk around the farm without feeling as if Butler’s likeness is watching over him, Thomas and the small staff of workers.

“Some days,” Walker says, “I see her and she gives me a smile. Some days ... Her eyes say, ‘Do better tomorrow.’ You can’t go anywhere without looking at Octavia before you leave.”

::

Thomas is reluctant to make herself the center of EARTHseed’s story, but she says another presence looms large over the farm — that of her late father, Lawrence “Jelly” Thomas. His name graces the same plaque that honors Carver and Tubman.

She grew up in rural Mercer County, Pa., and it was her father, a steel mill worker whose people hailed from rural Arkansas, who first instilled in her a respect for how humans affect the ecosystem.

A historian in Santa Barbara conducts tours to show that Latinos, who make up more than a third of the city’s population, are central to its existence.

He took Pandora and her sisters fishing and taught them the names of the minnows and worms he used to bait their hooks.

“He would just harvest wild things, which I guess he learned from his family, when we would be out,” she recalls.

The elder Thomas was otherwise stoic. But his close bond with nature was as clear then as Pandora’s passion for the environment is to those she guides around the farm.

Now Thomas, like her parents and those who came before, is the one paying it forward.

Thomas’ intentions aren’t lost on Felton Peterson, a member of Simley’s group. The 75-year-old is barely visible through the low branches of a mulberry tree as he searches for fruit.

“My grandparents had a farm,” he says. “Although I wasn’t one to work on a farm, what it means to have a farm and what they had to go through to feed themselves and/or others, you can’t put a price on it.”

As much as EARTHseed is about helping Black Californians prepare for an uncertain future, Peterson says, “this place will bring you back to your heritage.”