As the yellow bus carrying the Lassen High School girls’ volleyball team turned right on Highway 44, a sign flashed in its headlights: NEXT SERVICES 51 MILES.

It was just after 10 p.m. on a Thursday, and Bus 7221 was deep in the fire-scarred Lassen National Forest on a dark and winding two-lane highway, with no cellphone service.

The girls, wrapped in blankets and trying to sleep, were riding home to Susanville — a remote town of 13,700 in California’s northeast corner — after losing several matches to West Valley High School in Cottonwood, 119 miles away.

The drive took 2.5 hours each direction. There were long stretches with no gas stations, let alone electric vehicle chargers.

That’s why Lassen High sent a Blue Bird diesel bus, not one of its electric buses.

In California’s vast northern rural school districts, with their mountain passes and long, snowy winters, the typical electric bus’ range is not nearly enough. West Valley is one of Lassen High’s nearest athletic opponents. One of the farthest, Yreka High, is 169 miles away.

In this occasional series, we explore rural, conservative California through its struggling schools, which are cornerstones of life in small towns.

Yet California is pushing schools to get rid of their air-polluting diesel buses and swap them for battery-powered ones.

In October, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation requiring all newly purchased or leased school buses in California to be zero-emission starting in 2035. Rural school districts can have up to 10 additional years to fulfill the requirement, if they can prove the vehicles are impractical for their routes and terrain.

But even that generous time frame is unworkable unless electric bus technology significantly improves, rural school leaders say.

“The last thing we want to do is have kids stuck on the side of the road in a dead electric bus. Especially in the snow,” said Lassen Union High School District Supt. Morgan Nugent.

“We want to do our best for our environment. We live up here in the mountains. We want to see our resources protected. But we have to be realistic.”

In a state facing wildfires, droughts, extreme heat and other deadly consequences of the climate crisis, California lawmakers and air regulators have implemented some of the world’s most aggressive electric-vehicle mandates, to be phased in over the next two decades.

Newsom has tried to position California as a global leader in the fight against climate change. In October, he flew to China, where he met with President Xi Jinping and discussed electric municipal buses, battery storage and carbon markets with numerous government officials.

But here in California’s conservative northern reaches, residents say that urban Democrats like Newsom are failing to acknowledge the limitations of electric vehicles in rural areas.

Anyone who objects to electric vehicle mandates, they say, is dismissed as a climate change denier.

Going electric will be tough for all rural residents, considering the long distances they drive on lonely roads. For the humble yellow school bus, the hurdles are even greater, as are the consequences of running out of juice in the middle of nowhere.

“Would we all love electric buses? Absolutely. That would be great. But they just don’t work for us,” said Assemblywoman Megan Dahle, a Republican from Bieber, a Lassen County town of 260.

Dahle, vice chair of the California State Assembly Committee on Education, pushed for the rural schools’ deadline extension, which was not in the original version of Assembly Bill 579. But even that, she said, is not enough time for bus technology to improve or enough chargers to be installed.

She noted that chronic absenteeism is an issue in her district and that students who live far from campuses rely heavily on school transportation.

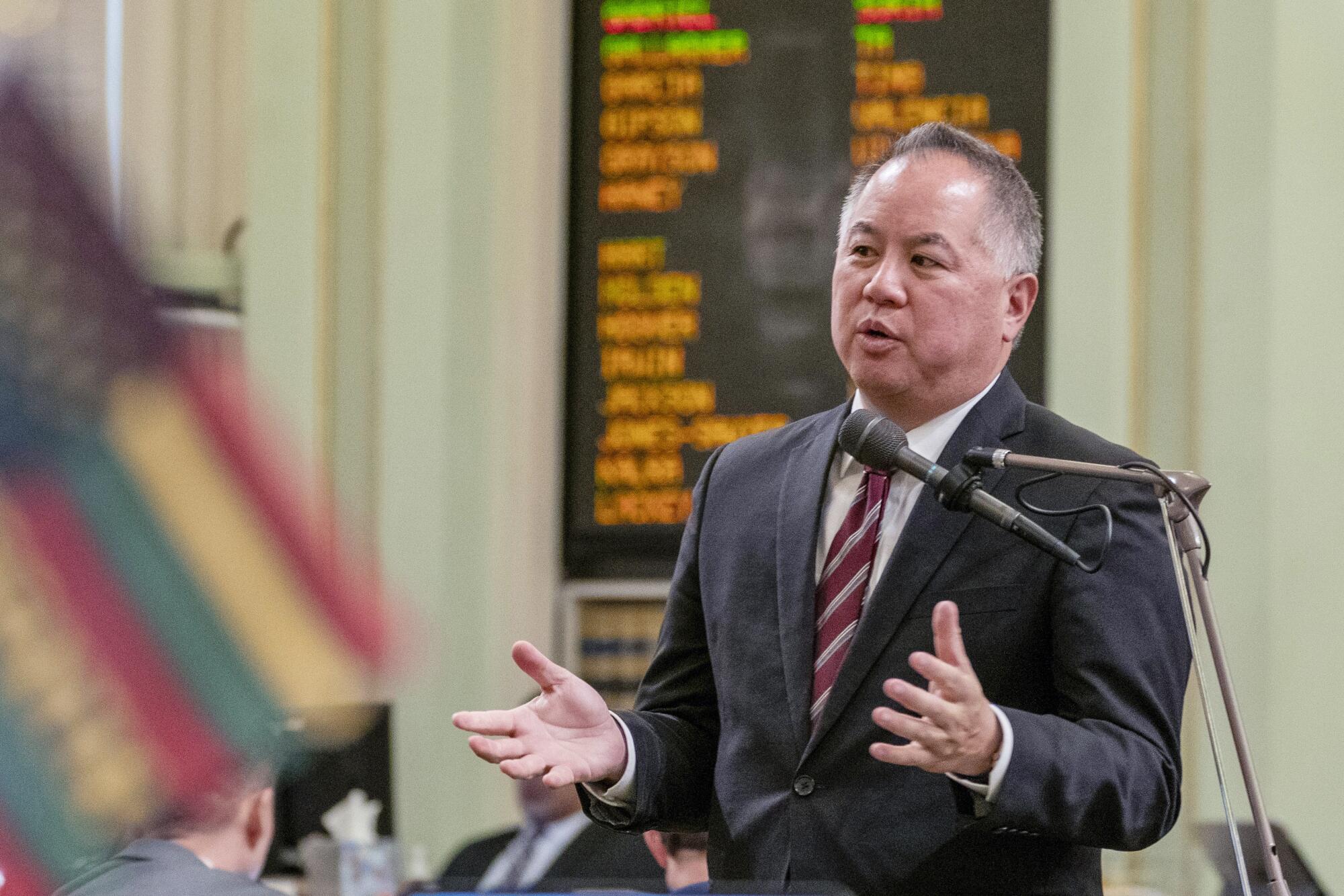

For Assemblyman Phil Ting, the San Francisco Democrat who wrote the school bus bill, the issue is not just air pollution but children’s exposure to carcinogenic diesel emissions.

“It’s even more important for rural areas because they’re on the bus longer,” he said.

Ting said the timeline is “absolutely not radical,” noting that schools can continue to use diesel buses purchased before the deadline until the end of their useful lives, which can be decades.

“I think they just don’t like being told what to do,” Ting said of school districts that pushed back against the bill.

He said the bill was needed or districts would “just delay, delay, delay. And obviously, it’s the students who suffer, and the environment suffers.”

On the Lassen High volleyball bus earlier that September day, heading the 119 miles to their matches at West Valley, the girls’ voices rose above the drone of the diesel engine.

“Your dad is hot!” one said.

“Leave my dad alone!” said another, laughing.

“OK, girls, let’s keep it appropriate!” shouted Gabi Newman, the junior varsity coach. At least the long drives are good for team bonding, she said, chuckling.

Newman, 24, played volleyball for Lassen High and is well-acquainted with the long rides, often in snow, in diesel buses with chains on their tires.

“I like that we’re looking at ways to use renewable energy,” she said. “I just don’t know how practical it will be for us.”

About 3% of the state’s school buses are electric, with about 600 zero-emission buses on the road and an additional 1,300 on order, the California Air Resources Board said in a statement to the Times.

To swap their diesel buses, schools have been receiving hefty government grants and other incentives that cover most, if not all, of the cost for new electric buses.

Over the last two decades, California has spent or allocated $1.2 billion to clean up its aging diesel school bus fleet, with an additional $1.8 billion planned over the next five years for zero-emission buses and charging infrastructure, according to the governor’s office.

Rural districts — as well as those with a high percentage of low-income students, foster youth and English language learners — will be prioritized for funding, the Air Resources Board said.

The board noted that children are “particularly vulnerable” to toxic diesel exhaust and that while school bus commutes are less than 10% of a child’s day, they contribute “33% of a child’s daily exposure to some air pollutants.”

In rural California, trips for extracurricular activities — sports, band competitions, clubs like Future Farmers of America — can be hours long.

The Quincy High School Trojans football team from Plumas County plays the Etna High School Lions in Siskiyou County. There are two possible routes through the mountains: a 233-mile, 4.5-hour drive mostly on Highway 89, or a 249-mile trip from the twisting Highway 36 to Interstate 5 that is nearly five hours long.

In basketball, the Modoc High School Braves in Alturas play the Trinity High School Wolves in Weaverville: 187 miles and a 3-hour-and-45-minute drive west.

“The technology is going to have to improve a lot before we would consider switching” to electric buses, said Tom O’Malley, superintendent of the Modoc Joint Unified School District.

O’Malley said his district recently was offered a $2.3 million federal grant to purchase electric buses — and turned it down.

The distance an electric school bus can drive on a single charge “can vary greatly based on climate, terrain, and driver habits,” Britton Smith, president of the Blue Bird Corporation, which manufactures school buses, said in a statement.

The advertised range for a Blue Bird electric school bus with a standard battery is up to 120 miles on a single charge, though some customers in California have reported a range of more than 130 miles, Smith said.

A more powerful battery with an expected range improvement of up to 20% has been developed but has not yet been fully tested, Smith added.

At the Lassen Union High School District, officials say their four battery-powered buses can go at most 93 miles on a full charge in peak weather conditions. The buses mostly stay parked.

For longer trips, Smith said, Blue Bird recommends its propane-powered school buses, which have a range of about 400 miles and “generate ten times less NOx [nitrogen oxide] emissions than the current EPA requirements.”

That type of bus will not be allowed under California’s new law. Nor will hybrid buses with a fossil fuel option, Ting said.

Another issue: public electric vehicle chargers, which are few and far between in rural California, are not practical for school buses, Smith said, because of their size and the locations of the chargers at places like grocery stores or strip malls.

Buses either need to make a round trip on a single charge, or campuses will have to install enough chargers for visiting schools.

The Bishop Unified School District, in rural Inyo County at the base of the Eastern Sierra, is among the more than 230 California public school districts and charter schools that have ordered at least one zero-emission school bus.

In 2020, Bishop swapped two old diesel buses for two new electric ones using grant money from the $423-million Volkswagen Environmental Mitigation Trust, said Todd Remley, the school district’s director of maintenance, operations and transportation. The trust is part of a massive legal settlement reached after the automaker’s emissions testing scandal.

Each bus cost more than $433,000, twice as much as a new diesel bus, but grants — $400,000, plus $5,000 for charging infrastructure — covered most of the cost, Remley said.

The old diesel buses were two decades old, had driven more than 300,000 miles and “smoked like a chimney,” spewing stinky black exhaust, Remley said.

Electric buses “seemed like a no-brainer. It seemed like a win-win-win,” Remley said. “And then? They don’t work so well.”

The first Blue Bird electric bus, which arrived in summer 2020, sometimes sped up too quickly when the motor surged. Other times, it went into “limp mode,” where it crept along but wouldn’t accelerate.

It has been repeatedly hauled away — on a flatbed trailer pulled by a diesel truck — and has spent months undergoing repairs, according to Remley.

Bishop Unified’s second electric Blue Bird came a few months later.

“The second bus worked a lot better. Until it caught on fire,” Remley said.

The cause of the fire, which started while the bus was plugged into its charger this August, remains under investigation, according to the Bishop Volunteer Fire Department.

Remley said security camera footage shows the bus slowly start smoking, then an arcing flame, “then more sparks and sparks.”

The district’s insurer, the vehicle manufacturer and the dealer are wrangling over who will pay for the charred bus, which remains out of service, Remley said.

Despite the troubles, Remley believes in electric school buses. The district uses the first bus — when it’s out of the shop — for in-town routes, charging it between the morning and afternoon drives.

Three more electric buses are on order.

Eastern Sierra Unified School District in Mono County also has two electric buses. Supt. Heidi Torix said charging equipment has caught fire with both.

“Unfortunately, our experience has not been positive, to say the least,” Torix said in an email.

For years after the Lassen district bought the four Blue Bird electric buses with grant money in 2019 and 2020, it had just one portable charger, which takes 14 hours to fully charge a bus.

The district now has three BTC Power charging systems, in addition to the portable one, after an arduous, years-long installation process that included upgrading the electrical grid and connecting the chargers to Wi-Fi to track usage for carbon credits.

The new chargers, which now await software programming, are not yet functional.

The buses themselves, like the ones in Bishop, have repeatedly been hauled off for warranty repairs — to Reno, 86 miles southeast.

For Supt. Nugent, the one-size-fits-all push for electric school buses is misguided and an example of the disconnect between California’s state government and rural denizens.

One early morning in late September, he drove along Highway 395, past trees still blackened from the 2021 Dixie fire, one of the biggest wildfires in California history. Nugent said he knows many people whose homes and land were burned.

“We’re spending billions of dollars on electric buses and watching our forests burn,” he said. “We’re spending the money on something that isn’t feasible right now.”

The money would be better spent, he said, on forest management.

It feels small, he said, to be talking about carbon credits for electric buses when the amount of greenhouse gases released by California’s massive wildfires in recent years has wiped out decades of air-quality gains.

Just after sunrise, Nugent pulled up to the post office in the tiny town of Milford. Cheri Lorenz soon rolled up in her red 2007 Chevy Silverado with her daughter Sophia, a sophomore at Lassen High, in the passenger seat, headphones on, cellphone in hand.

Every morning, mother and daughter drive 18 miles from the fire-damaged town of Doyle to Milford, where the diesel-powered school bus arrives around 6 a.m. to take students the 25 miles to Susanville.

Sophia, 15, wakes around 5 a.m. — an hour earlier if she wants to do her hair or makeup. During track season, when she rides the bus for out-of-town meets, she sometimes gets home after midnight.

Cheri Lorenz, a full-time caregiver for her own mother, said they plan their whole days around transportation.

“Lassen is the best high school in the area,” she said. “Those of us parents that can commute, we’ll do what we can. We’ll sacrifice.”

The school bus stop in Milford is a godsend because gas is so expensive in rural areas, said Lorenz, who quit a job as an Army supply technician and dipped into her retirement savings when her daughter started going to school in Susanville last year.

Asked about electric school buses, Lorenz started laughing.

“The school would have to invest heavily in diesel generators. Kids would be stranded,” she said.

The school district tried a few times to drive an electric bus to Milford. Last spring, a bus died six miles outside Susanville.

The district hauled out a diesel generator that ran for hours while the bus charged.

Electric buses can work for routes that are mostly in-town.

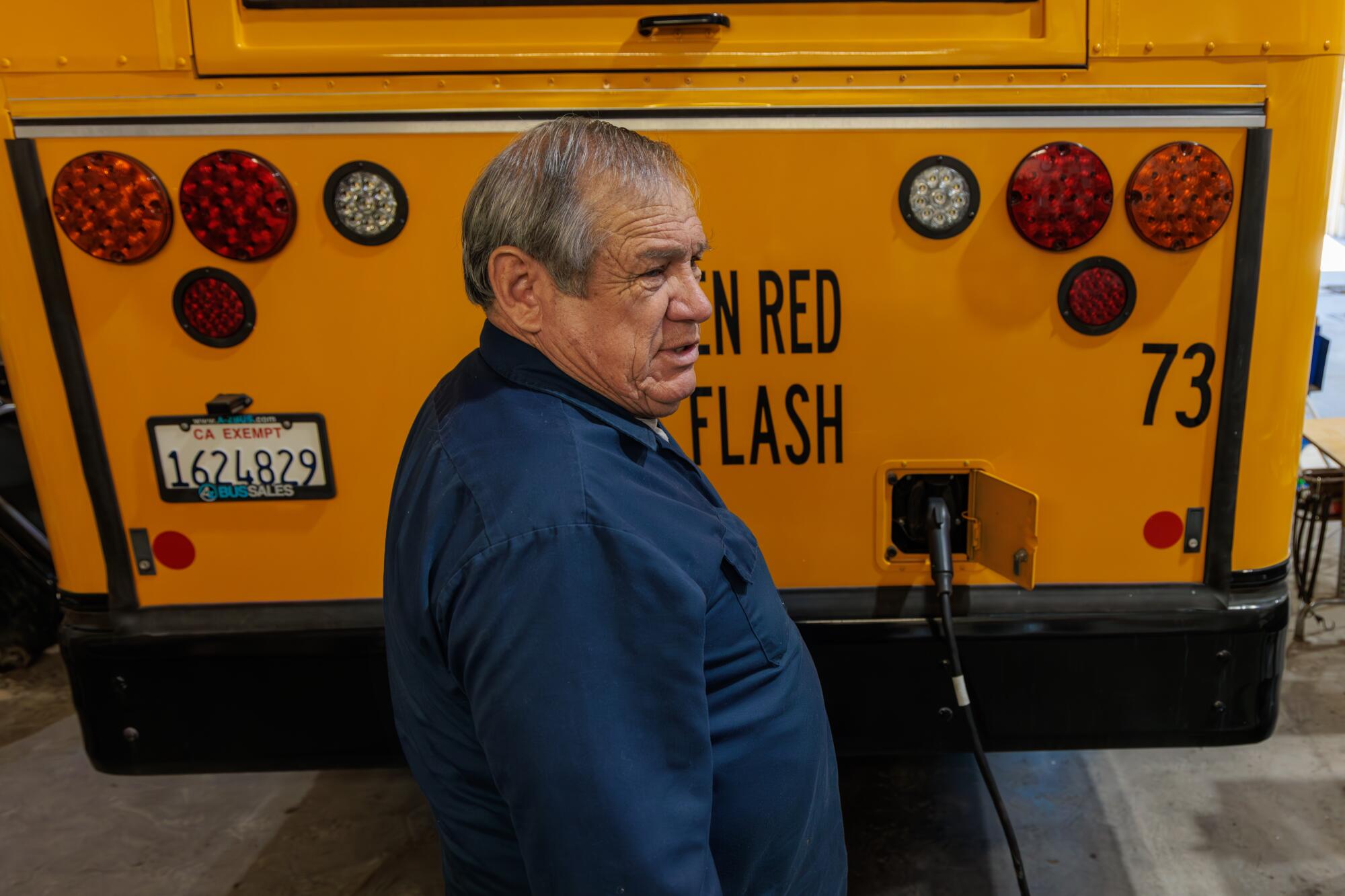

On a Wednesday afternoon in September, Joseph Smith was slowing Bus 73 to a stop near downtown Susanville when a noise rang out, drowning out the cussing middle-schoolers and giggling elementary school kids riding home from class.

It was a high-pitched squeal from the dash.

“Joe, it’s giving me a headache!” shouted a blond 7-year-old girl, fingers jammed in her ears. “Joe, if that beep comes on one more time, I’m screaming!”

It was the first time Smith had driven the electric bus in about three months. It spent all summer in a shop in Reno undergoing warranty repairs, and it was already acting up.

The alarm, which shut off a few minutes later, said the bus had low coolant. It was an error, said Smith, a longtime driver and the district’s school bus mechanic.

The engine is so quiet that it has a noisemaker — emitting a high-pitched hum like a synthesizer — as a safety measure, so pedestrians hear the bus rolling up.

The kids on board were not so quiet.

“Hey, Joe, I love you,” said a 5-year-old boy whose blond hair was combed into a fauxhawk. “Um, Joe, I’m a little hungry.”

Smith, a grandfather who knows many of the kids’ families, chuckled and kept a close eye on the mileage display. When he started the after-school route at 2:12 p.m, the dashboard on the fully-charged bus had said it could travel 91.3 miles.

His last stop, at a house in the Lassen National Forest — near a Smokey Bear sign that warned of high fire danger that day — was at 4:06 p.m, and he pulled into the bus barn 10 minutes later. He had driven 26 miles, zigzagging through town, and there were now 66 miles left on the charge.

It would take a few hours to fully charge the bus again.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.